AN ENVIRONMENTAL ‘DIRTY DOZEN’

One thread in the discussion of the Gulf environment involves ‘big pollution’ – the leading sources or source events in the modern era. This is an interesting area for debate. Sources may be specific (point source) or generic (non-point). A large oil spill from a ship has a point source, whereas the small gasoline leaks from 10,000 boats is non-point. The former is visible, traceable and easy to quantify whereas the latter is not. Another distinction is between pollution that is released on the water and land-based sources that flow into water. In the 1990s, when the United Nations debated regulatory approaches to ‘land-based sources of marine pollution’, it was estimated that the greater amount of marine pollution originated on land.

Another approach is to focus less on environmental ‘pollution’ and more on ‘ecology’. In some ways, this is a conceptual and political transition that unfolded slowly between the 1970s and the 2000s. The Gulf ecosystem pays more attention to the structures that tie the water body together. They are in large part bio-physical, centering in the energy and food webs through which life is supported. But there are also socio-political dimensions to ecosystems, since the natural resource components of an aquatic system can be utilized and modified by human use. Ecosystem change extends far wider than pollution alone.

These are features to keep in mind as we compile a potential list of the biggest Gulf of St. Lawrence pollution ‘events’. The dirty dozen that appears below combines point source and non-point factors. The sequence would no doubt change once we have a better grasp on the cumulative impacts of non-point sources, but this is for the future.

In no particular order, here is our list of candidates. We welcome further nominations.

- IRVING WHALE, SOUTHERN GULF WATERS

- SCOTT MARITIME/NORTHERN PULP MILL, NEW GLASGOW AND NORTHUMBERLAND STRAIT

- BELLEDUNE, NB, BAY OF CHALEUR

- MONTREAL SEWAGE, ST. LAWRENCE RIVER AND ESTUARY

- PEI FISH KILLS, RIVERS AND ESTUARIES

- TOXINS, ST. LAWRENCE RIVER AND ESTUARY

- PARLEE BEACH/SHEDIAC BAY CONTAMINATION, SOUTHEASTERN NEW BRUNSWICK

- TUNICATE AND SHELLFISH AQUACULTURE

- CANSO CAUSEWAY, SOUTHERN GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE

- SEISMIC TESTING FOR SUBSEA OIL AND GAS DEPOSITS, GULF-WIDE

- COLLAPSE OF NORTHERN COD POPULATION

- OIL LEAKAGE, ABANDONED WELLS, EASTERN GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE

1. IRVING WHALE, SOUTHERN GULF WATERS

In September of 1970, the fuel barge Irving Whale foundered while under tow in stormy conditions and sunk in 67m of water, northwest of Prince Edward Island. Owned by the Irving Corporation, it carried Bunker C oil as well as PCB fluids in the heating system. Approximately 600 to 800 tonnes escaped into Gulf waters before the cold waters reduced the oil viscosity and staunched the leaks. Nonetheless, beaches were fouled on the Magdalene Islands, prompting an extensive shore cleanup, while the rest of the leaked oil dissipated across an estimated 400 km2. The balance of the cargo remained on board. Thirty-five years later, in the face of renewed leakage and hull corrosion, the barge was recovered by Environment Canada, largely at public expense. A factor that accelerated the 1995 process was the belated discovery that PCB chemicals were on board as part of the cargo heating system, with their release posing an even more grave threat to Gulf waters.

Source: Nadeau, 2014.

2. SCOTT MARITIME/NORTHERN PULP MILL, NEW GLASGOW AND NORTHUMBERLAND STRAIT

In 1967 a sulphate pulp mill opened in New Glasgow. As part of the incentive package to lure Scott Paper of Philadelphia into the investment, the Government of Nova Scotia assumed responsibilities for the disposal of chemically infused mill effluents. The solution was to pipe the effluent under the East River to a tidal pool known as Boat Harbour. Located beside the Pictou Landing First Nation, the initial system included an open sewer and a settling pond, from which waters were released into Northumberland Strait. This began a half-century struggle between the First Nation, the mill and federal and provincial governments, over the types of treatment and compensation. In 2017 the province and the mill proposed a new system to release treated effluent directly into the waters of the Strait, a project that is being contested today.

Source: Radio Canada International, 2014.

3. BELLEDUNE, NB, BAY OF CHALEUR

The mid-1960s saw a burst of industrialization of northeastern New Brunswick centred on Belledune, a small coastal community. Several large projects in the region were constructed including a lead smelter by Brunswick Mining and Smelting (later owned by Noranda), a fertilizer plant, battery recycling plant, a coal-fired electricity generating facility, a gypsum plant, and a sawmill. The ensuing years have seen significant elevated levels of oral, respiratory, prostate and stomach cancers along with elevated levels of kidney and colorectal cancers. The culprit has been traced largely to lead, cadmium and arsenic emissions that have migrated to coastal waters where local seafood, which forms a large portion of the diet, has become contaminated. Complicating matters is the construction of a toxic waste incinerator in 2005 (which ceased operations a few years later) and plans for oil shipments by rail from Western Canada for export to international markets and a $1 billion iron ore processing facility. The health of the Bay and its people remains in a precarious condition.

Source: Belledune Smelter, National Pollutant Release Inventory, n.d.

4. MONTREAL SEWAGE, ST. LAWRENCE RIVER AND ESTUARY

The City of Montreal has been notorious for its dubious sewage disposal practices. Untreated sewage was dumped continually into the St. Lawrence River up until 1986, when the first primary treatment plant opened. Montreal has yet to install the secondary and tertiary systems common in many advanced municipalities. More recently this past was echoed in the 2015 event known as “flushgate”. The City of Montreal received federal approval to dump over 8 billion litres of raw sewage into the St. Lawrence River over the course of a week in October 2015. The “flush” was deemed necessary in order to perform maintenance on the system’s underground infrastructure with alternatives found to be too risky. The effects on marine life in the river and Gulf are unknown and the situation highlights acceptance of “dilution is the solution” mentality in society. A year later, in 2016, Quebec City did the same thing, dumping over 135 million litres of raw sewage in the St. Lawrence River in order to perform maintenance work on its sewage system. The situation underscores the lack of insufficient investment in key infrastructure to protect the environment.

Source: Remiorz (Canadian Press), 2015.

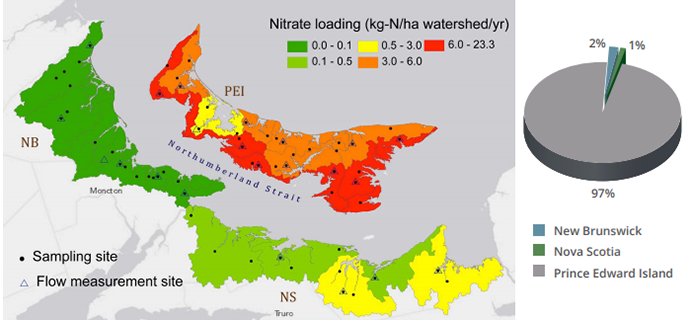

5. PEI FISH KILLS, RIVERS AND ESTUARIES

The potato is a staple of Island farming and in recent decades it has become a far more chemical intensive pursuit. When field fertilizers and insecticides are applied to fields in close proximity to rainstorms, the runoff into streams, rivers and estuaries can be fatal to fish. There are some fifty small watersheds on the Island and farms border almost all streams and rivers. Reports of fish kills seem to be a part of most Island summers, particularly in the central ‘potato belt’, and nitrate levels exceed Canadian guidelines in all Island estuaries. In addition to annual fish kills, excessive nutrient levels in estuaries have led to the near extinction of a rare strand of Irish moss, Chondrus crispus, at Basin Head, in eastern PEI. While most stakeholders acknowledge the existence of a problem, provincial authorities have moved gently in recent decades, relying on persuasion, guidelines, and farm client associations to encourage greater precaution in field treatments.

Source: Van Den Heuval et al., 2017.

6. TOXINS, ST. LAWRENCE RIVER AND ESTUARY

The St. Lawrence River, estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence is the recipient of industrial activity upstream in the Great Lakes basin. Here we find a toxic legacy from heavy industry such as steel production at Hamilton Harbour; industrial waste in the Cuyahoga River, Ohio, leading to at least 13 fires on the river; oil and chemical manufacturing along the St. Clair River; heavy metals and organic chemical contamination and sedimentation from the Maumee River basin; and, the Love Canal, a 70 acre industrial chemical dumpsite leading to significant elevated cancer rates and other persistent health concerns. Many other toxic sites exist along the shores of all the Great Lakes. Toxic chemicals include benzene, DDT, PCBs, toluene, TCP, acetyl, chlorobenzene, chloroform, dioxin along with nutrient loading from agricultural activities (fertilizers, pesticides) and sewage plants, chemical wastes from pulp and paper mills. What happens upstream matters downstream in the lower St. Lawrence and the Gulf with many mammal species negatively affected such as the Beluga and Right whales, not to mention the various fisheries. Addressing the Gulf environment means addressing upstream issues for which governments have been slow to respond.

Source: Environment Canada, 2013.

7. PARLEE BEACH/SHEDIAC BAY CONTAMINATION, SOUTHEASTERN NEW BRUNSWICK

Since at least the 1980s, recreational water quality has suffered from elevated levels of E. coli and Enterococci largely due to urbanization via the infilling of coastal wetlands and ineffective sewage treatment. Rather than adopt the Guidelines for Canadian Recreational Water Quality, in 2001 the province developed its own less stringent guidelines and transferred recreational water quality monitoring from the Office of the Public Health Officer to the Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Culture. Poor water quality results continued, and matters came to a head in 2015 when the public became aware of the extent of the problem. New studies revealed many factors at play including the construction of a restaurant on Parlee Beach without environmental assessment and a non-functioning sewage system for Parlee Beach Provincial Park for which its outlet remains unknown. In 2017, the Canadian Guidelines were adopted, and water quality assessment was moved back to the Public Health Office. In 2018, overhaul of the park’s sewage system was initiated among other initiatives.

Source: Fahmy and Harding, CBC News, 2018.

8. TUNICATE AND SHELLFISH AQUACULTURE

One of the most disruptive invasive species to arrive in Gulf waters is the clubbed tunicate. This is a marine invertebrate that attaches to substrate in shallow waters, grows rapidly and displaces rival organisms. The tunicate is thought to have arrived along with an ocean vessel that docked in Georgetown harbour or nearby PEI ports about 1997. One of the most common surfaces available to clubbed tunicate were aquaculture grow lines, which are suspended in shallow water. The rapid growth and reproduction of tunicates adds to the weight of the lines, retards mussel and oyster growth and complicates harvesting practices. This began at a time when shellfish aquaculture was experiencing rapid growth.

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2010.

9. CANSO CAUSEWAY, SOUTHERN GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE

In the early 1950s Angus L. Macdonald, Nova Scotia Premier and native Cape Bretoner, decided to build a car/rail causeway to replace the ferry service that linked the Island to the mainland. This involved the dumping of some 10 million tons of rock into the Strait of Canso, thereby blocking the natural water flows between the Atlantic and the Gulf. Completed in 1955, the causeway included a shallow draft ship canal and lock. Such major infrastructure was planned and delivered with none of the environmental sensitivities that emerged in the 1970s. While the full extent of impacts (to currents, ice cover, marine animal movements and others) has never been definitively established, there seems little doubt that the ecology of the southern Gulf was significantly altered.

Source: The Chronicle Herald, 2005.

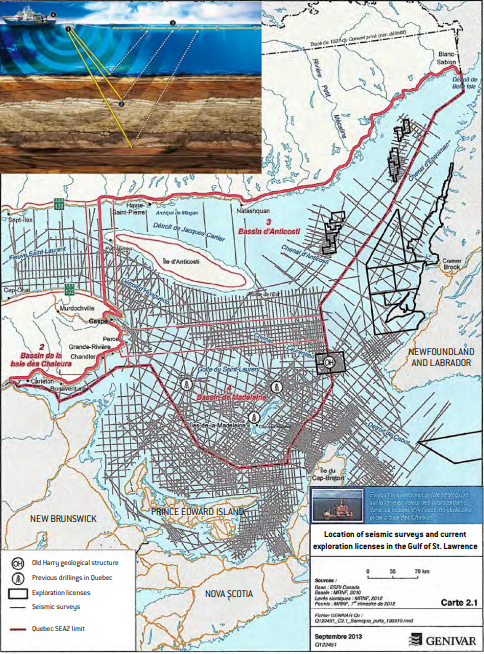

10. SEISMIC TESTING FOR SUBSEA OIL AND GAS DEPOSITS, GULF-WIDE

The Gulf of St. Lawrence has been a periodic target of hydrocarbon exploration since World War Two, though offshore production has yet to occur. The exploratory phases are not without impacts however. The opening phase is usually seismic testing, where sound waves are directed through sedimentary rocks and the ensuing images are studied for signs of oil and gas deposits. To do this, vessels tow arrays of listening instruments along designated routes while explosive percussion noise is set off at regular intervals. Given that offshore exploration began in North America in the 1950s, it is telling that the question of noise pollution impacts on aquatic animals was virtually neglected for forty years. A Cape Breton public inquiry in 2002 concluded that scientific evidence was thin and questions of mortality, injury and behavioural changes to aquatic animals (both mobile and sedentary) needed to be addressed on a priority basis before expanded exploration was approved.

Source: Genivar, 2013.

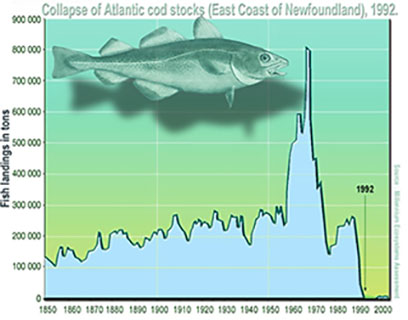

11. COLLAPSE OF NORTHERN COD POPULATION

Without doubt this is the most destructive and pervasive damage to the Gulf ecosystem in modern times. The north Atlantic cod population sustained a continuous fishery for five centuries. Yet in the past sixty years a combination of industrial scale groundfish trawling, fleet over-expansion, absent or flawed licence regulation, and political expediency enable as much fish to be taken in 2-3 cod generations as were fished in the previous 25-40. Belatedly, a moratorium was declared in 1992 but only after Gulf cod stocks were estimated to have fallen to 5-15 per cent of their historic size. The prolonged absence of cod has triggered dramatic transformations in the aquatic food web.

Source: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005.

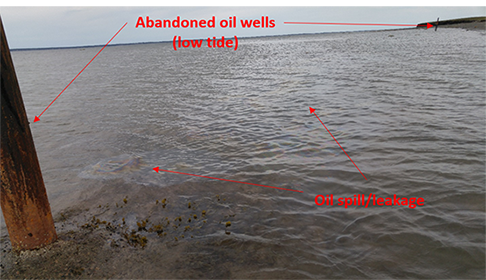

12. OIL LEAKAGE, ABANDONED WELLS, EASTERN GULF OF ST. LAWRENCE

Historical oil drilling activities have left a toxic legacy in the eastern Gulf of St. Lawrence centred on the Port au Port Peninsula at Shoal Point off the coast of western Newfoundland and Labrador. Oil leakage continues unabated from at least three abandoned oil wells with governments passing responsibility to each other for remediation. Newfoundland argues that the wells are located in the water and therefore a federal responsibility. The federal government counters that when the oil wells were drilled, they were on land and are hence a provincial responsibility. Coastal erosion has caused the wells to become water-based. At low tide, the wells can be seen protruding from the water but at high tide, the oil wells are submerged in at least one foot of water. Regardless, a sheen of oil can be found on the surface of the water, which has negatively affected local fisheries and the coastal environment.

Source: Levesque, 2017.

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.